Home > Implementation for Educators Blog

Long-Term Implementation Part III: Achieving Program Maintenance and Cost Savings During Funding Shortages

Maintaining high-fidelity practices for a decade and beyond is essential for maximizing impact and achieving significant cost savings. Maintenance stops the “churn” of abandoning one evidence-based practice after another, thereby accruing the repeated costs of purchasing materials and providing inadequate professional development, which results in low staff morale and turnover (Impact Workforce Solutions, 2025). In times of economic downturn, funding shortages, and inevitable staff turnover, the ability to sustain key programs for 10 or even 20 years offers a profound return on investment. This blog will examine the variables and behaviors that predict long-term maintenance, drawing on perspectives from SISEP state partners.

As Horner (2014) advises, organizations should “Implement with attention to the kernels, be more flexible about how you actually embed the practices, and over and over again, if you want to implement to scale, implement with the systems that will allow you to sustain things with high fidelity for a minimum of a decade.”

Sustainability vs. Maintenance: Understanding the Difference

It is important to make the distinction between sustainability and maintenance because they are often used interchangeably when, in fact, they mean two different things.

- Sustainability is the early effort to keep something from failing; it’s providing the support needed to continue over time. Merriam-Webster defines it as “using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged.”

- Maintenance is the subsequent, long-term ability to keep something in a specific, desired state through regular effort for the next generation. It focuses on ensuring “It” stays at the same level and continues with careful attention to contextual adaptation, following fidelity to a proven process. Merriam-Webster defines it as the act of “preserving from failure or decline.”

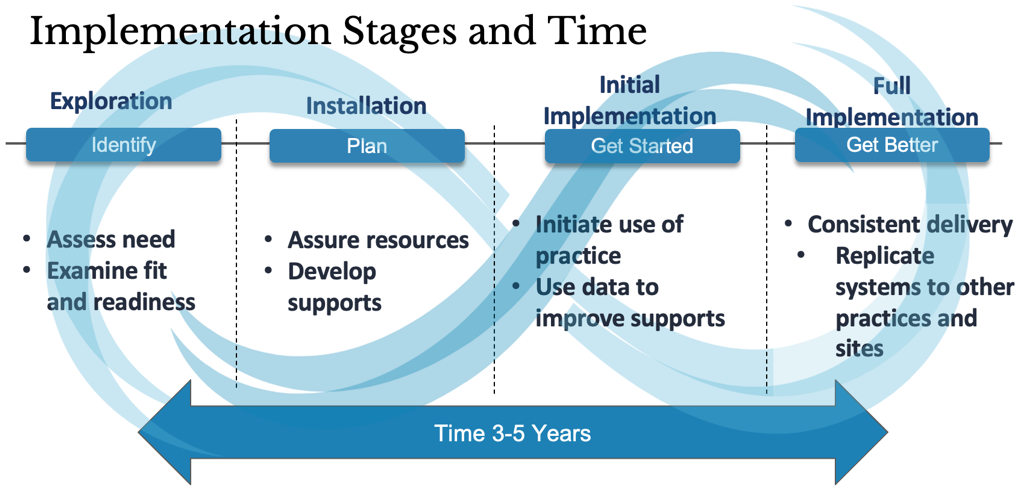

From Sustainability to Maintenance: The 3-5 Year Stage-Based Journey

It takes 3-5 years to reach full implementation and achieve desired outcomes (Metz & Bartley, 2012). Navigating the non-linear process of completing and continually revisiting Exploration, Installation, and Initial Implementation activities requires flexibility and constant attention to the needs of all learners, teachers, school staff, and leadership. These are the messy and awkward years – the time spent intentionally getting that “first, perfect pancake off the grill” by people with lived experience who bring valued perspective to the table.

During Exploration, Installation, and Initial Implementation, staff capacity and infrastructure are built. This is when a mindset and collective commitment for improvement are paramount to sustain team capacity (Fixsen et al., 2024). Teams take on the responsibility for building a strong infrastructure – a system of training, coaching, and data use that transforms the organization into a place where people’s needs are met. This environment creates a sense of belonging and ownership.

When a sense of belonging and ownership is palpable, a protective factor is created that prepares the system for inevitable turnover (Horner et al., 2017). Teams are ready to support new staff because they have built systems that support ongoing professional learning and sustained implementation (Earl, 2025).

As a result, staff are less likely to leave a supportive environment. The cost savings and financial returns are notable: teacher turnover in the US is estimated to be over $7.3 billion annually, with the cost of replacing a single teacher ranging from $9,000 – $25,000 (Learning Policy Institute, 2024).

Key implementation strategies used in sustainability pay off once an organization moves to maintenance (Ferlazzo, October 2024).

- Less is more when it comes to the programs a district uses. Alignment with core values is critical.

- The Initiative Inventory and Hexagon tools support teams in Exploration and Maintenance to select, deselect, and continue alignment of EBP.

- Meaningful opportunities for ongoing professional development driven by data and the expressed needs of staff.

- Caring Systems that empathize, protect, and respond to the needs of the people being served.

- The tool, Guidance for Engaging Critical Perspectives, ensures critical perspectives are at the table throughout the process and that all people remain actively engaged.

Paramount to active engagement is trusting relationships. As Allison Metz (2024) shares, “Yes, you can set up a fidelity monitoring system but you need people to trust the process, trust the data, trust the selection of the interventions, and you do all of that by demonstrating relationship building skills.” It takes relentless attention to building and sustaining trusting relationships to develop and maintain capacity and infrastructure – the bedrock of an organization’s ability to maintain its efforts for 10 years or more.

The Active Implementation Formula

The systems required for long-term sustainability and maintenance come to life within the Active Implementation Formula (AIF). The formula relies on three key factors:

Effective Practice (The What).

In exploration, a diverse team agrees upon a common philosophy and operational definition of their effective practice – their “it” – that aligns with their core values.

Effective Implementation (The How).

In installation, diverse teams co-create and expand the workforce capacity to prepare for turnover by establishing strong training, coaching, and data use systems that remove variance and spread a “less is more” mentality.

Enabling Context (The Doing).

In initial implementation, diverse teams use implementation and outcome data to continuously improve the systems and respond to the needs of the people; they keep the momentum going.

Socially Significant Outcomes (The Result).

This is the product when all factors are in place. It marks the moment 50% of staff are using the new program and meeting their aim in the first Transformation Zone, reaching a tipping point and moving into maintenance.

Reaching the Tipping Point: The Shift to Maintenance

When the product of the AIF is realized, it is to the credit of teachers and school staff who use a practice with fidelity. Equally important are the sponsors, and champions who ensure resource allocation and support. It takes a high-functioning, linked teaming structure to spread and scale an improvement until the systems and processes are institutionalized and embedded in policy. As McIntosh et al. (2009) suggest, if the valued outcomes are produced, the momentum to maintain effective implementation increases; if outcomes do not improve, maintenance is threatened.

- Gladwell (2006) defines the tipping point as the moment of critical mass, the boiling point. It’s when small, slow changes become irreversible, and ideas spread through the power of networks (like a Linked Teaming Structure).

Upon full implementation, a critical mass is achieved, and the focus shifts entirely to maintenance. Consistent delivery is a key variable, reliant on the capacity of staff (Arnold-Saritepe et al., 2023). Maintenance is required at both the individual and setting levels.

- Individual Level Maintenance: Defined as the long-term effects of a program on outcomes after implementation is complete. You might hear people say, “Our outcomes are stable because we never lose our intentionality.“

- Setting Level Maintenance: Defined as the extent to which a program becomes institutionalized and part of routine organizational practices and policies. You might hear people say, “This is how we do it here.“

Key variables include:

- The program’s enduring place in a community where it maintains a focus consistent with its original goals

- Effective collaboration among program stakeholders

- Staff involvement and integration with the program

- Organizational stability

- Fiscal oversight of program expenditures.

SISEP States Have Real-World Grit: Stories of 10+ year maintenance

Duckworth (2019) presents a compelling case for why some give up, and others persevere: it takes Grit. Grit is characterized by a strong passion to maintain determination and face challenges and setbacks head-on. Gritty people see obstacles as opportunities for continuous improvement. SISEP Active States have Grit. When they see a barrier, they solve it using iterative Improvement Cycles.

We highlight three SISEP states that have maintained their passion and determination for up to 29 years – they all possess grit.

The Kentucky Story. Active SISEP State and Long-term Partner: 2014-present

The Office of Special Education and Early Learning (OSEEL) at the Kentucky Department of Education partnered with SISEP to improve mathematics outcomes for Students with Disabilities. They built a highly effective linked teaming structure and mobilized the expertise of their regional partners to provide direct support to districts and their schools. Their efforts increased the percentage of students in special education meeting proficiency on the state summative assessment in four districts. Read their story – Ryan Jackson, et al, (2024). Today, the process is maintained and applied to English Language Arts and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports.

The Oregon Story: Active SISEP State 2006-2014

The Oregon Story began in 1996 when the Tigard-Tualatin School District (TTSD) created the Effective Behavioral Interventions & Supports (EBIS) model, blending PBIS and elementary literacy. TTSD’s ongoing support led to sustained reductions in discipline referrals and increased early reading benchmarks (Sadler & Sugai, 2009). In 2006, Oregon became an Active SISEP State and scaled the EBIS model in partnership with ORTII. The results were consistent with the original model (Chaparro et al., 2020), and the process is maintained, 29 years to date.

The Minnesota Story: Active SISEP State and Long-term Partner: 2008-present

For well over a decade, Minnesota has provided ongoing support for the use of PBIS and Check and Connect in their districts and schools. Read about the work – Kloos, et al, (2023). Eric Kloos, Ellen Nacik, John Gimpl, and the MDE Implementation Team (MIT) provide valuable insights into how the Minnesota Department of Education has achieved long term implementation in the Special Education Division’s Applied Learning. They’ve discovered that sustainability must be addressed from the Exploration phase forward, focusing on long-term stability across funding, strategic team partnerships, applied data use to improve, and recognizing typical patterns related to human factors. Read their full report.

Conclusion

As we can see, achieving maintenance of programs and practices does not happen overnight. It begins in Exploration when everyone’s eyes are on sustainability – a deep and collective desire to build and continuously improve the infrastructure. It’s the early signs of grit when an organization will not let something fail. Yes, maintenance takes grit – a willingness to face challenges head-on and not fall prey to a continuous cycle of giving up and moving to the next shiny thing when faced with challenges and setbacks.

Resources

- Active Implementation Overview (Module 1)

- Initiative Inventory

- Hexagon

- Guidance for Engaging Critical Perspectives

- Long-Term Implementation Part I: Mitigating the Impact of Turnover through Active Implementation (Earl, 2025)

- Long-Term Implementation Part II: Sustaining Implementation through Active Implementation (Walkins, 2025)

References

Arnold-Saritepe, A. M., Phillips, K. J., Taylor, S. A., Gomes-Ng, S., Lo, M., & Daly, S. (2023). Generalization and maintenance. Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis for Children with Autism: Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment, 415–433.

Chaparro, E. A., Smolkowski, K., & Jackson, K. R. (2020). Scaling up and integrating effective behavioral and instructional support systems (EBISS): A study of one state’s professional development efforts. Learning Disability Quarterly, 43(1), 4–17.

Duckworth, A. (2019). Grit: Why passion and resilience are the secrets to success. NIDA Journal of Language and Communication, 24(35), 105–106.

Ferlazzo, L. (2024 October 23). Want to retain teachers? Here’s what districts and schools can do. EducationWeek Blog. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-want-to-retain-teachers-heres-what-districts-and-schools-can-do/2024/10

Fixsen, D. L., Van Dyke, M. K., & Blase, K. A. (2024). Implementation science for evidence-based policy. In B. C. Welsh, S. N. Zane, & D. P. Mears (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Crime and Justice Policy (pp. 58–75): Oxford University Press.

Horner, R. (2014, June 5). Scaling up evidence based practices [Invited guest]. Oregon Department of Education, Salem, Oregon.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Fixsen, D. L. (2017). Implementing effective educational practices at scales of social importance. Clinical child and family psychology review, 20(1), 25–35.

Gladwell, M. (2006). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. Little, Brown.

Impact Workforce Solutions (2025, November, 10). The true costs of employee churn https://www.impactws.com/the-true-costs-of-employee-churn/

Learning Policy Institute (2024, September, 18). What’s the Cost of Teacher Turnover? https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/2024-whats-cost-teacher-turnover-factsheet

McIntosh, K., Horner, R. H., & Sugai, G. (2009). Sustainability of systems-level evidence-based practices in schools: Current knowledge and future directions. Handbook of positive behavior support, 327–352.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Maintain. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/maintain

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Sustain. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved November 10, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sustainability

Metz, A. (2024, February 15). Implementation – Is building relationships strategy? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULc8ehsaefw

Metz, A., & Bartley, L. (2012). Active implementation frameworks for program success. Zero to three, 32(4), 11–18.

Sadler, C., & Sugai, G. (2009). Effective behavior and instructional support: A district model for early identification and prevention of reading and behavior problems. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(1), 35–46.