Home > Implementation for Educators Blog

Regional Education Agencies: The Critical Link Between the State and the Classroom

Have you ever tried to do something new without any support? Perhaps you wrote a children’s book that was never published because the system was so unknown, and honestly, a bit intimidating. An experienced author knows that it takes a team at the organizational, regional, and local levels to support publication. In fact, some suggest it can take up to 32 organizational structures to get your book in the hands of the reader (Laubeon, 2015). One may ask, where is the leverage point within those 32 entities that maximizes efficiency and effectiveness? History would tell us it is a regional entity. In fact, as far back as the 1880s, a regional structure and strategy were used in business, human services, and education. Our forepeople recognized the importance of regional entities in adopting and adapting a common approach in local contexts. They saw how regional entities provided a bridge between governing organizations and local communities. In the early 1800s, a regional education service agency was established in Delaware and Oregon to support local school districts (Stephens, 1973). Today, we build on that wisdom and use examples from practice to demonstrate how regional entities serve as the critical link in testing the innovation of governing agencies to determine what works, for whom, and under what conditions, at the local level within their unique context.

Let’s take education as an example. Improving student outcomes is the goal of every State Education Agency (SEA). Achieving this goal requires continuous improvement of instructional strategies that meet the evolving demands of an ever-changing student, teacher, and administrative demographic. Improving student outcomes requires ongoing support for teachers, school staff, students, and their families. This support is structured through a hierarchical system, ranging from the state to the classroom. If we think about this hierarchy in terms of a linked teaming structure, we can easily see the implementation challenge when any one team is missing, because one level without the other is insufficient for effective and sustained change (Tommeraas & Ogden, 2015).

Barrier to Effective Implementation: A Simple Multiplier Effect

The United States has 50 State Education Agencies (SEA) that support approximately 14,000 school districts, 98,000 schools, 3 million teachers, and 50 million students. While the national average shown below is not representative of a given state it does demonstrate an implementation barrier using a simple multiplier effect. For example,

- 1 state supports

- 280 districts, that support

- 1,960 schools,

- 58,000 teachers, and

- 999,000 students.

The ratios are daunting and highlight a significant management and support challenge, especially since the 1:280 state-to-district ratio is far beyond the recommendation of 1:8 cited by Fixsen et al. (2014).

Take a moment to calculate your state’s ratio.

Is it beyond the recommended 1:8 ratio?

Proposed Structural Solution: The Regional Entity

We propose that the critical link between the state and the classroom is the regional entity. Instead of one state managing 280 districts, the regional entity can create a manageable ratio.

- 1 state supports

- 14 regional entities that support

- 20 districts

- 140 schools

- 600 teachers, and

- 10,200 students

Leveraging Sustainable Change in a Linked Teaming Structure

In education, the critical link between the State Education Agency (SEA), its districts, and schools is the regional education agency. At every level of the system, administrators with authority allocate resources and sponsor the work of teams while champions advocate for the needs of those they serve. Teams at every level of the system make a collective commitment to continuous improvement. They strengthen the implementation infrastructure so it is durable and resilient to turnover and the dynamic nature of the education system. To accomplish this, they remove barriers to their regional and state sponsors, including those of the teacher, school, and district. Then, they report and support viable solutions at the local level. Our regional partners ensure and deliver the professional development, training, and coaching districts, schools, and teachers require to support our children in pre-kindergarten to grade 12 and beyond (Polk, 2021) to meet state and local goals.

Some states have longstanding partnerships with their regional entities that they continue to grow. Other states have a regional fee-for-service structure, yet they may choose to design a regional structure independent of the region to support the use of a specific innovation. Other states, however, do not have a regional structure, so they create a state-supported regional structure. With any attempt at effective change, we know that attention to context and the structure that will be usable and scalable at the local level is critical. Three of SISEP’s long-standing partners provide examples of how they leverage regional partners to effectively utilize their identified innovations and programs, thereby improving outcomes for their target populations.

Kentucky, 2014-2025 sustaining partner

Together, Kentucky’s regional cooperatives and Special Education Regional Technical Assistance Centers (SERTACs) build the capacity of LEAs to serve all students, and students who receive special education and related services. In “Leading By Doing,” Kentucky educators describe their implementation journey and the improved mathematics outcomes that resulted.

When we asked Dr. Dionne Bates—KVEC SERTAC Director, Implementation and Improvement Lead—how the regional structure in Kentucky provides the critical link between the classroom and the state, she replied:

The Kentucky Valley Education Cooperative (KVEC) Special Education Regional Technical Assistance Center (SERTAC) is a regional service agency that extends the work led by the Kentucky Department of Education’s Office of Special Education and Early Learning (OSEEL), focusing on improving outcomes for students with disabilities. In partnership with OSEEL, the KVEC SERTAC provides district and school-level support in alignment with the State Identified Measurable Goal (SiMR) to improve Mathematics and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) through engaging classroom learning environments.

- The first step in the work begins with superintendent and district leaders engaging in data analysis as part of the exploration phase, using the Implementation Science Framework. The data findings drive the decision-making process, allowing districts and schools to pinpoint and prioritize their focus based on their own identified needs.

- The next step is to build capacity at the district and school level. KVEC works alongside school leaders, providing training tailored to the utilization and fidelity of the Kentucky Model Implementation Tool (KMIT), and delivers personalized training for school personnel specific to the identified innovation. The leaders join our team to conduct walkthroughs, and the SERTAC provides follow-up coaching and support to teachers while building the capacity of school-level staff to continue the work far beyond the SERTAC support and services.

- The final step in this process is ensuring continuous improvement. School-level teams routinely review student achievement and KMIT data. By engaging with the data, they are building data-driven practices and are true partners in the transformation of teaching and learning systems in their classrooms.

We have witnessed the impact of the work in our districts, and so have they. Students are growing and thriving.

Michigan, 2015-2024 sustaining partner

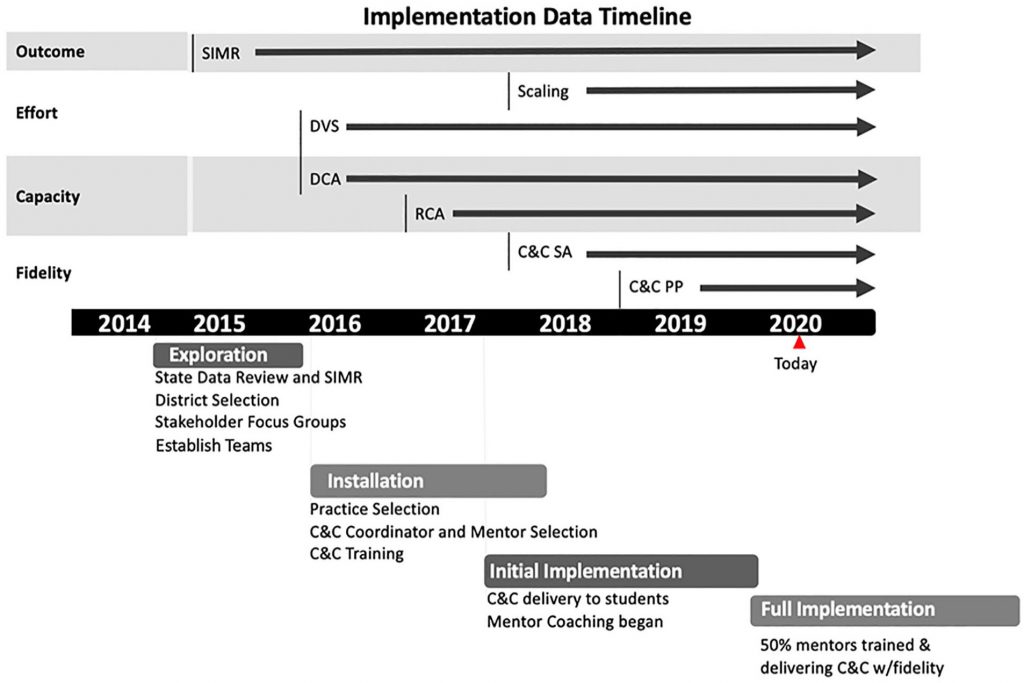

Michigan’s public education system is structured with local school districts, operating within a framework of 57 Intermediate School Districts (ISDs) or Regional Educational Service Agencies (RESAs). These ISDs provide support and services to local districts. In, Transforming a Regional Education Agency, they describe their implementation journey.

When we asked Brian Jones—Retired Executive Director, Lenawee ISD—how their regional structure has evolved since joining the SISEP work in 2017, he explained:

Lenawee ISD is a small regional education service agency that supports eleven rural local school districts, ranging in size from 340 students to 2,700 students. Prior to partnering with the Michigan Department of Education and the SISEP Center on a Multi Tiered System of Support (MTSS) project, Lenawee ISD had a good relationship with its local districts, providing special education itinerant services, hosting a countywide Career and Technical Education (CTE) program, and general education consulting services (literacy, math, and science).

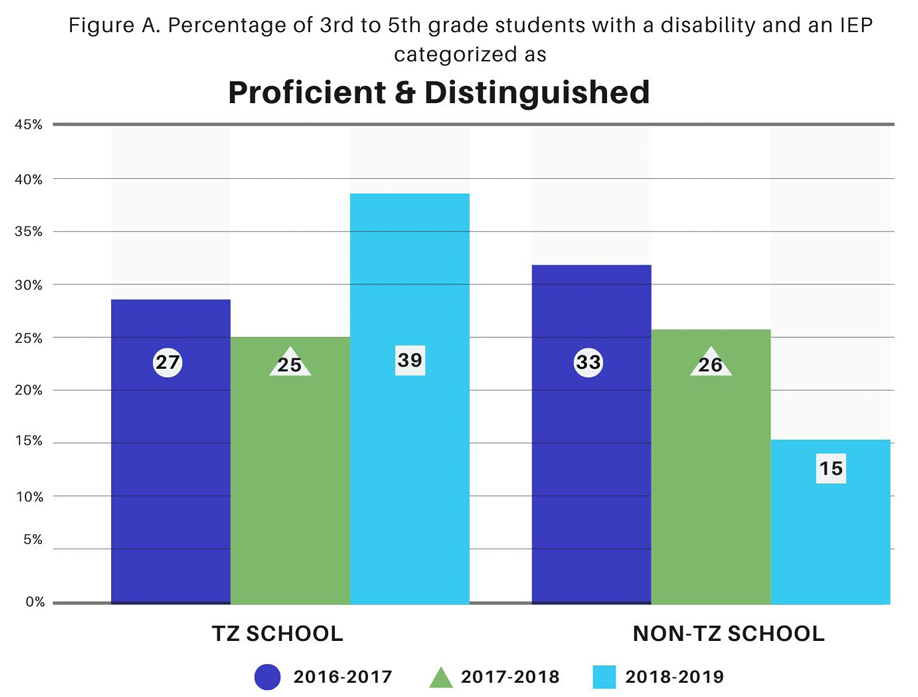

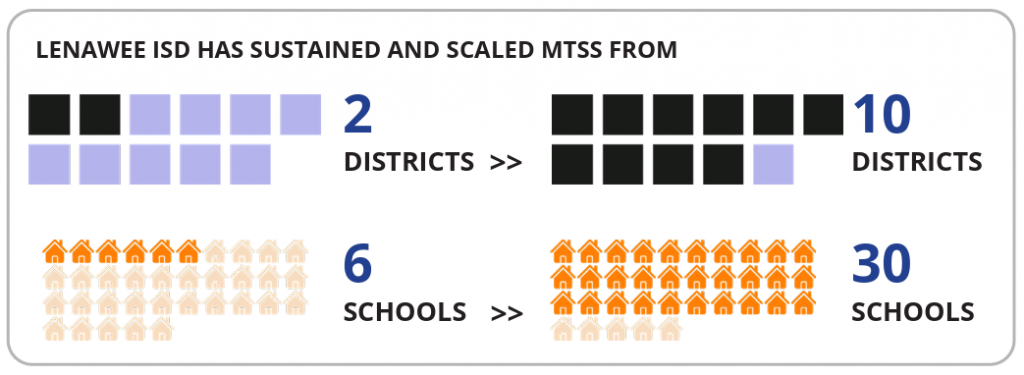

- Since joining the Transformation Zone, Lenawee ISD has supported ten of the eleven local districts in implementing MTSS district systems along with either PBIS or Reading as effective innovations. This work included supporting District Implementation Teams (DIT) with ISD Systems Coaches. These coaches supported DIT Coordinators in developing agendas, understanding the content, and navigating district culture. The coaches also attended monthly DIT meetings, often providing mini-lessons in implementation science.

This embedded model of coaching enabled Lenawee ISD to access local districts that were not previously available. Coaches are now often asked to attend district-level cabinet meetings, help plan professional learning, and serve as a sounding board to district administrators.

- Partnering with local districts on a significant undertaking, such as developing district MTSS systems, has allowed ISD staff to develop deep bonds and trust with those they support. These deeper relationships have opened doors to new projects while improving support to the local districts. Some of these new projects include developing a countywide collaborative curriculum directors’ group that meets monthly and a data review group focused on improving student achievement and attendance, with cross-district professional learning planned.

Minnesota, 2008-2018 Sustaining Partner

In “Developing Implementation Capacity,” Minnesota describes their implementation journey and the achievement of their State Systemic Improvement Plan (SSIP) goal of improving graduation rates for Black and American Indian Students with disabilities, as well as how their regional functions support District Partnerships for Results.

The Minnesota Department of Education, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) work developed a regional structure to provide more local contextual implementation support (including training, coaching, evaluation); the regions work together along with a state Leadership Team to ensure all areas of our MN PBIS Blueprint are addressed. When we asked Minnesota whether the regional structure for using the PBIS blueprint sustained improved end user outcomes as they scaled their identified programs and practices to local districts and schools, they said their regional PBIS structures are:

- sustainably funded,

- aligned around a common Usable Innovation (PBIS),

- active in the collection and use of data, and

- linked from school to district to region to state.

The MN PBIS work uses a regional structure to provide more local contextual implementation supports (including training, coaching, evaluation). The regions work together along with a state Leadership Team to ensure all areas of our MN PBIS Blueprint are addressed. Our blueprint is different than the suggested national one, since we focus on applied functional “buckets of work” including:

- Training/coaching new schools

- Supporting sustaining schools to become exemplary schools/districts

- Re-engaging schools that have not continued to collect fidelity data

- Engaging districts/co-ops when a critical mass of schools in the district have been through training

- Advanced Tiers

- Working with IHEs

- Educator prep programs to ensure applied PBIS examples are used, exemplar teams identified to present in classes

- Ensuring that when licensure standards come up for review, we advocate for PBIS competencies to be included

Building statewide trainer capacity (pulling from exemplary school districts/schools) is key to developing external coaching and evaluation capacity.

The Regional Structure Develops Capacity for Scaling-up

Regional Structures support the growth of implementation efforts. As we can see from our regional partners in Kentucky, Michigan, and Minnesota, they have developed the capacity of their districts, schools, and teachers to spread and scale their chosen programs and practices, meeting common state-identified goals. Kentucky ensures continuous improvement by utilizing data to enhance the capacity of schools and districts to sustain their efforts. Michigan stresses the importance of deeper relationships and ongoing coaching support. Minnesota suggests that improved end-user outcomes are achieved through sustainable funding and the use of data from schools to districts, regions, and the state. The question remains, and an important variable to consider is, whether the same improved results can be sustained over time as programs are scaled to additional sites.

In conclusion, research shows that when there is a strong regional structure in place, proven practices can be successfully scaled without losing their effectiveness. Typically, a “scale-up penalty” occurs when the implementation process becomes more complex and less controlled as it expands, leading to a decrease in behavioral change and outcomes. However, a study in Norway (Tommeraas & Ogden, 2015) that used the active implementation approach (Fixsen et al., 2013) found no evidence of this penalty. With the support of national and regional teams, a Parent Training program was implemented across local sites, and the data showed that behavioral outcomes remained consistent as the program scaled. This suggests that a well-established regional structure may be key to maintaining quality and ensuring successful outcomes throughout the scale-up process.

Resources

- The components of the Active Implementation Formula are defined by the five (5) Active Implementation Frameworks (AIF). The AIFs are the key ingredients necessary to achieve socially significant student outcomes.

- Implementation Teams support the full, effective, and sustained use of effective instruction and behavior methods. Linked Implementation Teams define an infrastructure to help assure dramatically and consistently improved student outcomes.

Leveraging Change in State Education Systems

- Effective implementation capacity is essential to improving education through the creation of implementation capacity for evidence-based practices benefitting students, especially those with disabilities.

References

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K., Horner, R., Sims, B., & Sugai, G. (2009). Scaling-up brief. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina.

Fixsen, D., Blase, K., Metz, A., & Van Dyke, M. (2013). Statewide implementation of evidence-based programs. Exceptional Children, 79(2), 213–230.

Kloos, E., Nacik, E., & Ward, C. (2023). Developing implementation capacity of a state education agency to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 34(2), 127–136.

Laubeon, S. (2015, May 18). How many people are engaged in publishing your book? https://stevelaube.com/how-many-people-are-involved-in-publishing-your-book/

Polk, L., (2021, June 2). Educational Service Agencies: Review of selected/related literature. https://www.aesa.us/2021/06/02/educational-service-agencies-review-of-selected-related-literature/

Stephens, E. R. (1973). The emergence of the Regional Educational Service Agency concept in education: Dominant organizational patterns and programming thrusts. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED084693.pdf

Tommeraas, T., & Ogden, T. (2017). Is there a scale-up penalty? Testing behavioral change in the scaling up of parent management training in Norway. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 203–216.

Welsh, B. C., Sullivan, C. J., & Olds, D. L. (2010). When early crime prevention goes to scale: a new look at the evidence. Prevention Science, 11(2), 115–125. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0159-4.